Old Testament literature displays a wide range of attitudes towards wealth in various contexts. But an examination of the distribution of these comments reveals a development in thought over time. The basic tripartite division of the Old Testament into Law, Prophets and Writings provides a rough time trajectory for this study. Viewed in this fashion, there is a clear increase in comments on wealth as time progresses and a diversification of thought at the same time.

The earliest strands clearly depict wealth as a blessing from God bestowed on the righteous. One aspect of prophetic literature hangs on to this notion while trying to explain the loss of this blessing. The prophets also stress the responsibility to the poor in the community and note that many of these poor are righteous. The writings take up some of the questions posed by this disconnect between the lot in life of the righteous and the wicked versus the earlier promises. At the same, the prophets and writings contain passages that assume the basic world view that God rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked.

The intertestamental literature adds consideration of eschatology and the afterlife to the question of wealth. There are clear condemnations of the wealthy, and some indication that wealth is obtained by being wicked and not as a blessing from God. Developments threaten to see wealth as intrinsically bad.

Christianity ends up balancing these views by seeing wealth as a part of God’s good creation for the betterment of the community, but not necessarily an indication of divine favor. Over time Christianity deftly collects these disparate attitudes towards wealth into a cohesive theology.

Wealth in the Old Testament

The distribution of references to wealth in the Old Testament shows an increasing frequency from Torah to Prophets to the Writings.[1] And even as the number of references increases, they are still but a small portion in the overall volume of literature. Clearly topic of wealth is not the focus of any of the books, but the subject is obviously of increasing interest over time.

The nature of the references to wealth becomes more diverse as they increase in frequency. The foundational thought in Hebrew scriptures is that wealth is a blessing from God to those who follow the law (Duet. 5:15; Ex. 20:12). As time progresses and the early promises are unfulfilled the Old Testament must begin to deal with this disconnect between the promise of prosperity and the reality in the nation. The wisdom tradition in Israel does this in part by contact with other nations. Greek thought ascribes wealth to those who are cunning, not righteous.[2] This provides one avenue of exploration, especially in the intertestamental period.

The Law

The covenant narratives promise wealth as a blessing for following God’s leadership. The patriarchs are wealthy by God’s gift to the detriment of those that oppose them. Indeed, the patriarchs are portrayed as an ideal to exceed.[3]

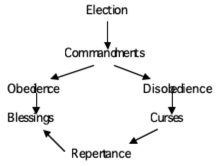

The covenant model sets up the basic understanding of relationship to God for Israel. The elect are given the commandments. Obedience leads to blessings and disobedience to curses, with an opportunity to repent.[4]

Ultimately, this simple understanding fails to explain the lived reality as Israel progresses in history. The blessings of God are denied to Israel and the wicked appear to be blessed.

The Prophets

The prophetic literature seeks to deal with these issues. The prophets include the oppression of the poor among the sins leading to God’s punishment in exile.[5] Thus in some cases wealth is a sign of sinful behavior in breaking God’s law. The law says that one must provide for the priests, levites and the poor.[6] By oppressing the poor they were breaking the covenant. These breaches of the covenant on the part of the nation then cause the disaster of the exile.[7] At the same time, the prophets assume that prosperity will return as God’s gift if Israel repents. In this sense we are still operating under the basic covenant model as described above.[8]

The Writings

The writings really begin to wrestle with the question of the wicked rich. The covenant theology model is still present in many of the passages on wealth. But additional thoughts are offered beyond these established positions as well. The wisdom literature is a particularly strong in this regard. The international nature of wisdom study allows these scribes to consider the issue of the wealthy wicked from different perspectives and attempt to harmonize these views with the fundamentals of Israel’s covenant theology.[9]

Two representative examples illustrate the nature of the transition, Proverbs and Sirach. Proverbs represents a composite work created relatively early in the post-exilic period while Sirach is a heavily Greek influenced and late work. Proverbs represents the start of the transition mixing very old elements with foreign thoughts.[10] Sirach comes at the close of the Old Testament canon prior to the intertestamental literature heavily influenced by eschatology and the afterlife.[11] At the same time both Proverbs and Sirach share an affinity in literary type.[12]

The opening chapters of Proverbs place wealth and power as among the primary goals in life. Even when extolling the beauty of wisdom over the pursuit of wealth and power, they assume that wealth and power come with the attainment of wisdom and that wealth and power cannot be adequately exercised with wisdom.[13]

But Proverbs paints an ambiguous picture of the wealthy. They have security (10:15), popularity (14:20), and power (22:7). But are arrogant (18:23) and conceited (28:11). The wealthy are defined in terms of their relationship to the poor in Proverbs.[14]

Proverbs also warns the reader against placing too much stock in the acquisition of wealth. One should concentrate on the more important aspects of life because wealth is fleeting and will only pass to someone else on your demise.[15]

There is a strain in Proverbs that strikes for the balance in the middle. The desire of the wise should be for the middle ground, neither wealthy nor poor (30:7-9). That too great a treasure would bring trouble (15:16). That wealth can bring conflict to a home (15:17; 17:1). Wealth is only good if achieved honestly. Righteousness is valued over wealth (16:8).

Sirach also insists that wealth must be free from sin in acquisition but notes that the community respects the wealthy and they have many friends (13:15-24). This poem equates the wicked rich as feeding on the poor like the wolf on lambs. In a later poem Sirach asks if anyone tested by greed can be found perfect (31:1-11). The merchant is assumed to be a cheat out of greed (26:29-27:3). Wealth is described as a fleeting possession that passes with this life. The miser simply collects wealth for someone else to use after they are gone (14:3-19). These passages speak to a strong assumption of evil doing on the part of the wealthy. But the equation is not absolute. Sirach declares the wealthy blessed that are able to overcome these temptations (31:8-10).

Sirach acknowledges that wealth can be the direct result of sinful behavior but stops well short of equating wealth with sin.[16] Other intertestamental literature does seem to make this equation. The earlier stream of tradition that sees wealth as a blessing from God won’t allow the Biblical wisdom books to go that far.[17] The Biblical wisdom literature is layering nuances of explanation for the exceptions and is not ready to reverse the original premise. The intertestamental literature does make that next step in many cases.

Intertestamental Literature

Jewish intertestamental literature had a lasting effect on Christian theological writings and the New Testament itself.[18] This literature makes ample use of the contrast between the righteous and the sinners. Eschatology is predominant in the literature and apocalyptic forms are common. The basic view is that God will set the world right in the end with punishment for the sinners and justification for the righteous.[19] In most of these stories the rich and powerful are part of the problem.

A representative example would be 1 Enoch. In 1 Enoch we have the typical intertestamental literature characteristics and a work that has seen widespread acceptance and use in Christian circles.[20] In 1 Enoch 92-105 there is a combination of two apocalyptic addresses and a series of woes declaring the coming punishment of the wicked. Enoch plays the role of the wise man in preparing the righteous for the coming events of the end times.[21] The woes detail the punishment coming for those wicked that persecute the righteous. Likewise the righteous will receive a special spiritual joy in the afterlife from God for holding true.[22] The wicked are specifically condemned because of their illicit acquisition of wealth and their religious apostasy. The crimes outlined here describe an identical social situation to that of Sirach above, but the condemnation is much stronger.[23]

Early Christian attittude towards Wealth

By the time of the early church the popular transformation in attitude towards wealth is complete. Not only is wealth no longer considered a blessing for the righteous, but also wealth must be rescued from being labeled bad in and of itself. Part of the growth of Christianity as a religion early on is due to its concern with economic matters. This was unique in Greco-Roman religions. They taught on property, money and labor issues. Wealth has no ethical value but a religious one. These are good products and elements created by good for the good of all.[24] From an ethical perspective there are three basic problems with the accumulation of wealth for the early Church Fathers: the avarice of the wealthy, the dishonesty with which the wealth is obtained and the irrational uses to which the wealth is put.[25] The fathers wonder how the rich will be saved. They can achieve this by working towards the ideal of service with their wealth. They can start by giving up the superfluous in their lives and convert that into charity. This will start them on the road to spiritual growth and freedom from their wealth. He does hold out that greed will be punished in the final judgement. That intention is important in this process. Wealth is a hindrance to salvation and only careful management and use of the wealth can overcome this barrier.[26]

Wealth is good in appearance only. It stimulates a desire for perishable and transient things and is thus an unnatural passion. Desire for wealth is not natural or necessary but is superfluous. Wealth makes you a captive of soulless possessions and distracts from the service of god.[27] The Christian Church in the east had a long history of philanthropic support.[28] This was even legislated by the councils both local and ecumenical. The first council of Nicea’s seventieth canon mandated the establishment of hospitals by the church. The Chalcedon council extended this to orphanages and houses for the poor and widows.[29] When Constantine legalized the Church he also took the Church under his patronage as emperor. He contributed to the Church directly and he followed the Church by contributing to the poor, widows and orphans as they did. This led many wealthy in the empire to emulate the emperor as a way of currying favor.[30]

Patronage was a system of relationships between a lesser and a greater person. Friendship is a key virtue in the culture between a patron and their client. The greater would provide for the educated lesser ranks. They in turn would provide service in their way to the benefactor. The Fathers have this system of patronage friendship in mind when he speaks of Christians becoming friends of God. In the same way that the rich and powerful have a friend in the emperor, the Christian is a friend of God. In the same way that a political friend intercedes for favors, the Christian can intercede in prayer before God.[31]

Ultimately, the rejection of personal wealth is held up as the ideal in monasticism. By the fourth century Fathers are even suggesting that all Christians are called to a monastic style of life, even married people in the city. They should live the monastic ideal as much as possible especially the lack of material possession. They see the acquisitive nature of man as the root of all social evil. The entire material world belongs to the lord for the benefit of all, not to become a possession of a single person.[32]

Conclusion

The Christian tradition continues to struggle with this basic balancing act regarding wealth. Wealth is a source of many good deeds and support for the community, but avarice and acquisitiveness are among the most powerful motivations for evil conduct in the world. Striking this balance of acknowledging the good of God’s creation in wealth and what it can accomplish while avoiding the evils that easily spring from the same is no easy task. Judging whether particular cases of wealth are examples of God’s blessing or human avarice is not easy. This is especially true when the visible conduct is not clearly wrong or harmful. Under these circumstances, the answer can only lie in the heart of the possessor of wealth. In any case, clearly the tradition of stewardship demands that wealth be shared with the larger community regardless of its source.

[1] The distribution is 6 in Torah, 23 in History, 34 in Prophets and 93 in wisdom literature according to Conrad Boerma, The rich, the poor and the Bible (Philadelphia: Westminister Press, 1980), 10.

[2] Ibid., 11.

[3]At the same time the wealth of the patriarchs is clearly a communal wealth and not merely a personal estate. The narratives also make clear that all material wealth belongs to God by virtue of his creation. Charles Ryder Smith, The Bible doctrine of wealth and work in its historical evolution (London: The Epworth Press, 1924), 21-29.

[4] The articulation of covenant theology and figure are from George W. E. Nickelsburg, Ancient Judaism and Christian origins : diversity, continuity, and transformation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003), 32-33.

[5] See Amos 4:1; Hab. 2:9; Jer. 5:27; 6:6; 22:13; 22:17; Ezek. 45:9; Mal. 3:5; Mich. 2:1; Zech. 7:10

[6] There are three basic categories of commands: allowances to ease suffering, laws of protection from abuse and positive commands to help. See the discussion in Smith, 55-59. For a detailed discussion of how these regulations were understood in the Jewish tradition see Jacob Neusner, The economics of the Mishnah, Chicago studies in the history of Judaism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

[7] Oppression of the poor through various economic crimes is but one of the crimes of the nation. Lunn points out that the focus on economic crimes is sometimes over emphasized in modern commentaries. The condemnation of idol worship, syncretism and lack of trust in God by forming foreign alliances are all more prominent transgressions than the economic ones. John Lunn, “On riches in the Bible and the west today,” Faith & Economics 39 (2002): 21.

[8] While the model is the same, there is a deepening understanding of righteousness as an end in and of itself, not simply a means to national prosperity. Smith, 127-29.

[9] For a discussion of the international character of Biblical wisdom literature see James L. Crenshaw, Old Testament wisdom : an introduction, Rev. and enl. ed. (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998). For a discussion of the relationship between Biblical wisdom books and Greek philosophy see John Joseph Collins, Jewish wisdom in the Hellenistic age (Louisville, Ky.: Westminister John Knox Press, 1997), 222-32. That the Greek influence is small and clearly secondary to ANE influence in wisdom literature is argued by Martin Hengel, Judaism and Hellenism : studies in their encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period, vol. 1 (London: SCM Press, 1974), 107-10. In any case, we clearly see influences beyond the borders of Israel, whatever their source.

[10] Proverbs contains both the oldest and newest word forms in the Hebrew scripture. This demonstrates a solid mixture of ancient with newer elements in the final editing of the book. Harold C. Washington, Wealth and poverty in the Instruction of Amenemope and the Hebrew Proverbs(Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1994), 116-22. For a detailed discussion of dating, structure and composition of Proverbs see the introduction in Richard J. Clifford, Proverbs : a commentary, The Old Testament library (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999). Proverbs shows evidence of multiple editorial recensions from an early date. These can be detected in the surviving translations and early discussions on the text. More information on the recension and version activity in Proverbs is discussed in Richard J. Clifford, “Observations on the texts and versions of Proverbs,” in Wisdom, you are my sister : studies in honor of Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm., on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, ed. Roland Edmund Murphy and Michael L. Barré, The Catholic Biblical quarterly. Monograph series (Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1997). For a discussion of the differences in organization of Proverbs LXX and MT version with a chart of the displacements see Washington, 125-27.

[11] For a detailed discussion of dating, structure and composition of Sirach see the introduction in R.A.F. Mackenzie, Sirach, ed. Carroll Stuhlmueller and Martin McNamara, Old Testament message, vol. 19 (Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, 1983).

[12] Although Sirach is a more polished example of the literary form according to George W. E. Nickelsburg, Jewish literature between the Bible and the Mishnah : a historical and literary introduction (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981), 55-57.

[13] Roger N. Whybray, Wealth and poverty in the book of Proverbs, Journal for the study of the Old Testament. Supplement Series, vol. 99 (Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1990), 99-106.

[14] There is a clear comparison of the wealthy to the poor at work in Proverbs. Fo the nine clear references to the wealthy all but one is part of a comparison to the poor. Roger N. Whybray, “Poverty, wealth, and point of view in Proverbs,” Expository Times 100, no. 9 (1989): 334.

[15] This attitude to avoid excessive avarice is common in Egyptian wisdom literature as well according to Whybray, Wealth and poverty, 115.

[16] Sirach’s attitude towards wealth is ambiguous but not entirely negative according to Crenshaw, 147.

[17] For an outline of Sirach passages affirming the covenant model of blessing and curses with regard to wealth see Nickelsburg, Jewish literature between the Bible and the Mishnah : a historical and literary introduction, 63-64.

[18] The Gospel of Luke and many of Paul’s letters share language and worldview with intertestamental literature Nickelsburg, Ancient Judaism and Christian origins : diversity, continuity, and transformation, 42-43.

[19] For a fuller discussion of the literary genre and worldview of intertestamental literature including 1 Enoch see Frederick J. Murphy, The religious world of Jesus: an introduction to second temple Palestinean Judaism (Nashville: Abingdon, 1991), 163-86.

[20] Sirach uses Enoch as the inclusio for his review of the righteous ancestors in Israel, the list begins and ends with Enoch 44:16 and 49:14. James C. VanderKam, Enoch, a man for all generations, Studies on personalities of the Old Testament (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1995), 92-93. 1 Enoch is quoted as authoritative in the New Testament at Jude 14-15. The Son of Man concept that appears in all four gospels, Paul’s letters, Hebrews, 1 &2 Peter and Revelation is also taken from 1 Enoch expressions of the concept George W. E. Nickelsburg and James C. VanderKam, 1 Enoch : a new translation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004), 83-86. For a fuller discussion on 1 Enoch’s influence on Luke’s negative portrayal of the rich see George W. E. Nickelsburg, “Revisiting the rich and the poor in 1 Enoch 92-105 and the Gospel according to Luke,” in George W.E. Nickelsburg in perspective : an ongoing dialogue of learning, ed. George W. E. Nickelsburg, Jacob Neusner, and Alan J. Avery-Peck, Supplements to the Journal for the study of Judaism (Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2003), 563-68. 1 Enoch is included in the canon of scripture by Ethiopian Orthodox, along with Jubilees. 1 Enoch is considered one of the prophets and inserted before Job. Nickelsburg and VanderKam, 1 Enoch : a new translation, 15-16. The apostolic fathers and patristic use of 1 Enoch is also extensive. See the references in Nickelsburg and VanderKam, 1 Enoch : a new translation, 87-95.

[21] James C. VanderKam, Enoch and the growth of an apocalyptic tradition, The Catholic Biblical quarterly. Monograph series, vol. 16 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1984), 170-74.

[22] There is no resurrection of the body, but a clear promise of a special and better afterlife for those that are true to God in this world with a punishment to sinners as well. VanderKam, Enoch, a man for all generations, 93-94.

[23] An extensive comparison of the social situation of 1 Enoch and Sirach is presented by Richard A. Horsley, “Social relations and social conflict in the Epistle of Enoch,” in For a later generation : the transformation of tradition in Israel, early Judaism, and early Christianity, ed. Randal A. Argall, Beverly Bow, and Rodney Alan Werline (Harrisburg, Pa: Trinity Press International, 2000), 104-15. Sirach’s role as a teacher of wealthy students softens his commentary according to Randal A. Argall, 1 Enoch and Sirach : a comparative literary and conceptual analysis of the themes of revelation, creation, and judgment, Early Judaism and its literature ; no. 08 (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995), 252-54. Whatever the source of the increase in animosity towards the wealthy from Sirach to 1 Enoch, the progression itself is clear.

[24] Typical examples are Theophilus, Ad Aut., Liber II, passim. Origen In ep. Ad Rom., IV, 9; Clem. Of Alex., Paed., II, 12; Cyprian, De Op. Et eleem., XXV; Novatian, De Trinitate, I. Igino Giordani and Alba Israel Zizzamia, The social message of the early church fathers (Paterson, N.J.,: St.Anthony guild press, 1944), 254-55.

[25] Anastassios Karayiannis, “The Eastern Christian Fathers (350-400 A.D.) on the redistribution of wealth,” History of Political Economy 26, no. 1 (1994): 43-47. The criticism of wealth in many of the early church fathers seems to rest on the assumption that the gaining of wealth was illicit. There were manifest injustice and exploitation in the acquisition of wealth. The ascetic ideal was held up as the true soldier of Christ would travel light in this world. We see this thought as early as Tertullian, the didiche and the shepherd of hermas and Gnostic acts of Thomas. Carl A. Volz, Faith and practice in the early church: Foundations for contemporary theology (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1983), 209-10-11.

[26] Christopher A. Hall, Reading scripture with the church fathers, ed. Thomas Oden, Ancient Christian Commentary (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 1998), 175-76. The sin of wealth is not in the possession, but in the misuse. Your attitude towards wealth is the critical element. This attitude can be discerned by how you use wealth. Wealth can overwhelm the mind and lead to avarice. The salvific use of wealth is in charity. When you recognize that the world is passing wealth has no more power over you. Rebecca H. Weaver, “Wealth and poverty in the early church,” Interpretation 41, no. 4 (1987): 377. Georges Florovsky, “St. John Chrysostom: the prophet of charity,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly, no. 3-4 (1955): 39.

[27] Georges Florovsky, The Eastern Fathers of the fourth century, trans. Catherine Edmunds, The Collected Works, vol. 7 (Vaduz, Europa: Büchervertriebsanstalt, 1987), 249.

[28] For a complete discussion of Almsgiving in the Byzantine imperial culture see Demetrios J. Constantelos, Byzantine philanthropy and social welfare (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1968), 3-64. The extension of this culture into ecclesiastical institutions is discussed in Constantelos, 67-110.

[29] Constantelos, 69-70. One of Christ’s titles in Byzantine liturgical services is filanqropos ‘lover of mankind.’ This appellation is frequent in vespers and matins. This even gave rise to a separate devotional service with this title in the post-reformation age. For Chrysostom the terms filanqropia and agaph are interchangeable. He uses both to refer to the feelings of love that Christ has for Christians. But for Chrysostom this love joins with God’s justice his judgement. They are two sides to the same coin. God’s love is tempered with his justice and God’s justice is meted out in accordance with ones participation in that love. This is not a simple sentimental love of God for the Christian but a love that contains and demands just action. Constantelos, 34.

[30] Rowan A. Greer, Broken lights and mended lives: theology and common life in the early Church (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1986), 131.

[31] Michael Sherwin, “Friends at the table of the Lord: friendship with God and the transformation of patronage in the thought of John Chrysostom,” New Blackfriars 85, no. 998 (2004): 387-88. For a more complete description of the classical patronage scenario see David Konstan, “Patrons and friends,” Classical Philology 90 (1995): 329-30.

[32] Georges Florovsky, Christianity and culture, trans. Catherine Edmunds, The Collected Works, vol. 2 (Vaduz, Europa: Büchervertriebsanstalt, 1974), 33-34.

Bibliography

Argall, Randal A. 1 Enoch and Sirach : a comparative literary and conceptual analysis of the themes of revelation, creation, and judgment. Early Judaism and its literature ; no. 08. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995.

Boerma, Conrad. The rich, the poor and the Bible. Philadelphia: Westminister Press, 1980.

Clifford, Richard J. “Observations on the texts and versions of Proverbs.” In Wisdom, you are my sister : studies in honor of Roland E. Murphy, O. Carm., on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, ed. Roland Edmund Murphy and Michael L. Barré, The Catholic Biblical quarterly. Monograph series. Vol. 29, 47-61. Washington, DC: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1997.

________. Proverbs : a commentary. The Old Testament library. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1999.

Collins, John Joseph. Jewish wisdom in the Hellenistic age. Louisville, Ky.: Westminister John Knox Press, 1997.

Constantelos, Demetrios J. Byzantine philanthropy and social welfare. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1968.

Crenshaw, James L. Old Testament wisdom : an introduction. Rev. and enl. ed. Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998.

Florovsky, Georges. “St. John Chrysostom: the prophet of charity.” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly, no. 3-4 (1955): 37-42.

________. Christianity and culture. Translated by Catherine Edmunds. Vol. 2 The Collected Works. Vaduz, Europa: Büchervertriebsanstalt, 1974.

________. The Eastern Fathers of the fourth century. Translated by Catherine Edmunds. Vol. 7 The Collected Works. Vaduz, Europa: Büchervertriebsanstalt, 1987.

Giordani, Igino, and Alba Israel Zizzamia. The social message of the early church fathers. Paterson, N.J.,: St.Anthony guild press, 1944.

Greer, Rowan A. Broken lights and mended lives: theology and common life in the early Church. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1986.

Hall, Christopher A. Reading scripture with the church fathers. Ancient Christian Commentary, ed. Thomas Oden. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 1998.

Hengel, Martin. Judaism and Hellenism : studies in their encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period. Vol. 1. London: SCM Press, 1974.

Horsley, Richard A. “Social relations and social conflict in the Epistle of Enoch.” In For a later generation : the transformation of tradition in Israel, early Judaism, and early Christianity, ed. Randal A. Argall, Beverly Bow and Rodney Alan Werline, 100-16. Harrisburg, Pa: Trinity Press International, 2000.

Karayiannis, Anastassios. “The Eastern Christian Fathers (350-400 A.D.) on the redistribution of wealth.” History of Political Economy 26, no. 1 (1994): 39-67.

Konstan, David. “Patrons and friends.” Classical Philology 90 (1995): 328-42.

Lunn, John. “On riches in the Bible and the west today.” Faith & Economics 39 (2002): 14-22.

Mackenzie, R.A.F. Sirach. Vol. 19 Old Testament message, ed. Carroll Stuhlmueller and Martin McNamara. Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, 1983.

Murphy, Frederick J. The religious world of Jesus: an introduction to second temple Palestinean Judaism. Nashville: Abingdon, 1991.

Neusner, Jacob. The economics of the Mishnah. Chicago studies in the history of Judaism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Nickelsburg, George W. E. Jewish literature between the Bible and the Mishnah : a historical and literary introduction. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981.

________. Ancient Judaism and Christian origins : diversity, continuity, and transformation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003.

________. “Revisiting the rich and the poor in 1 Enoch 92-105 and the Gospel according to Luke.” In George W.E. Nickelsburg in perspective : an ongoing dialogue of learning, ed. George W. E. Nickelsburg, Jacob Neusner and Alan J. Avery-Peck, Supplements to the Journal for the study of Judaism. Vol. 80, 547-71. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2003.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., and James C. VanderKam. 1 Enoch : a new translation. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004.

Sherwin, Michael. “Friends at the table of the Lord: friendship with God and the transformation of patronage in the thought of John Chrysostom.” New Blackfriars 85, no. 998 (2004): 387-98.

Smith, Charles Ryder. The Bible doctrine of wealth and work in its historical evolution. London: The Epworth Press, 1924.

VanderKam, James C. Enoch and the growth of an apocalyptic tradition. Vol. 16 The Catholic Biblical quarterly. Monograph series. Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1984.

________. Enoch, a man for all generations. Studies on personalities of the Old Testament. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1995.

Volz, Carl A. Faith and practice in the early church: Foundations for contemporary theology. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1983.

Washington, Harold C. Wealth and poverty in the Instruction of Amenemope and the Hebrew Proverbs. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1994.

Weaver, Rebecca H. “Wealth and poverty in the early church.” Interpretation 41, no. 4 (1987): 368-81.

Whybray, Roger N. “Poverty, wealth, and point of view in Proverbs.” Expository Times 100, no. 9 (1989): 332-36.

________. Wealth and poverty in the book of Proverbs. Vol. 99 Journal for the study of the Old Testament. Supplement Series. Sheffield, England: JSOT Press, 1990.

For Lent this year I am reflecting each day on a different New Testament passage touching on wealth. It looks to me in just gathering the list that love of money mentioned numerous times as getting in the way to path to heaven, but actual wealthy people are almost always spoken well of. There are 4 ways to become wealth 1) inherit it, 2) win the lottery, 3) earn it honestly, 4) earn it dishonestly. 3 out of 4 seem ok. Your thoughts?

The source of the wealth has not traditionally been the issue in early Christianity. Rather the focus is on the actions of the wealthy and the various requirements for charity as I note here.

Steve