Joseph of Arimathea figures prominently in a number of liturgical contexts in the Byzantine tradition. This paper will examine the scriptural, liturgical and patristic traditions of the Eastern Church and this important figure at the death of Christ. These traditions will be examined in light of what modern source, form, textual and historical criticism offer on the story of Joseph. The primary scripture passage used liturgically for Joseph is the pericope from Mark.

Mark 15:42-47 RSV

And when evening had come, since it was the day of Preparation, that is, the day before the Sabbath, Joseph of Arimathea, a respected member of the council, who was also himself looking for the kingdom of God, took courage and went to Pilate, and asked for the body of Jesus. And Pilate wondered if he were already dead; and summoning the centurion, he asked him whether he was already dead. And when he learned from the centurion that he was dead, he granted the body to Joseph. And he bought a linen shroud, and taking him down, wrapped him in the linen shroud, and laid him in a tomb which had been hewn out of the rock; and he rolled a stone against the door of the tomb. Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joses saw where he was laid.

The entire passion narrative in Mark consists of eleven units (including the resurrection account). Conjunctions with time references frequently mark these transitions. The narrative moves briskly from the evening in the garden to the morning of the empty tomb. These units vary in length only slightly and all are short. Mark changes the action and characters from scene to scene as well. We can use the time, character and linguistic markers to separate the units of the passion narrative. [1]

The burial unit of the passion narrative in Mark begins with a conjunction and a time reference. We also see the introduction of a new character, Joseph of Arimathea. The unit ends right before the next time reference with the mention of the characters of the next unit. This transitional scene takes us from the death on the cross to the location of the resurrection to come on Sunday. Mark gives us the rationale for the burial and the reason that the women who will first bear witness to the resurrection can know where to look for the body. The passage also provides affirmation of the death of Jesus from the secular authorities of the centurion and Pilate.

Text Critical Issues

The Byzantine Text form of the Markan burial story is remarkably uniform. There are only three minor variations in the text, a word order change, a spelling variant and a verbal form change.[2] None of these offers significant alternate texts to consider. There are similarly minor variations from the Byzantine Text form in the critical texts. These involve variant names, addition or deletion of articles and minor shifts in word forms.[3],[4] Likewise, none of these variants creates alternative texts to consider for this discussion.

Source and Redaction issues

The burial pericope is contained in all four Gospels. The parallel passages are Matthew 27:57-61, Luke 23:50-56 and John 19:38-42. The quadruple attestation of the burial story provides strong support for the fundamental historicity of the event. The details differ in all of the versions. But even those prone to doubt historical events in the Gospels, like Bultmann, place the burial event in the category of history.[5] Nevertheless, the scene itself, and all of the details in each version, remain the servant of the evangelist in the passion narrative as a whole. Each pericope notes that Joseph buried Jesus, but the details of the scene help each evangelist move the story along in their own Gospel. Looking at the elements in common and different in the narratives in combination with the role the scene serves in each Gospel, allows us to make some source and redaction comments.

| Mark 15:42-47 | Matthew 27:57-61 | Luke 23:50-56 | John 19:38-42 |

| After this Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple of Jesus, but secretly, for fear of the Jews, asked Pilate that he might take away the body of Jesus, and Pilate gave him leave. So he came and took away his body. Nicodemus also, who had at first come to him by night, came bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about a hundred pounds’ weight. They took the body of Jesus, and bound it in linen cloths with the spices, as is the burial custom of the Jews. Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb where no one had ever been laid. So because of the Jewish day of Preparation, as the tomb was close at hand, they laid Jesus there. | When it was evening, there came a rich man from Arimathea, named Joseph, who also was a disciple of Jesus. He went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus. Then Pilate ordered it to be given to him. And Joseph took the body, and wrapped it in a clean linen shroud, and laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn in the rock; and he rolled a great stone to the door of the tomb, and departed. Mary Magdalene and the other Mary were there, sitting opposite the sepulchre. | Now there was a man named Joseph from the Jewish town of Arimathea. He was a member of the council, a good and righteous man, who had not consented to their purpose and deed, and he was looking for the kingdom of God. This man went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus. Then he took it down and wrapped it in a linen shroud, and laid him in a rock-hewn tomb, where no one had ever yet been laid. It was the day of Preparation, and the sabbath was beginning. The women who had come with him from Galilee followed, and saw the tomb, and how his body was laid; then they returned, and prepared spices and ointments. On the sabbath they rested according to the commandment. | After this Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple of Jesus, but secretly, for fear of the Jews, asked Pilate that he might take away the body of Jesus, and Pilate gave him leave. So he came and took away his body. Nicodemus also, who had at first come to him by night, came bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about a hundred pounds’ weight. They took the body of Jesus, and bound it in linen cloths with the spices, as is the burial custom of the Jews. Now in the place where he was crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb where no one had ever been laid. So because of the Jewish day of Preparation, as the tomb was close at hand, they laid Jesus there. |

Table of differences

| Matthew | Luke | John |

| Plus | Minus | Plus | Minus | Plus | Minus |

| Sabbath | Evening | Evening Sabbath | |||

| Disciple Rich man | Member council | Jewish town | Disciple—secretly for fear of Jews | Member of council | |

| Take away (instead of asked for) | |||||

| Dialog with Pilate | Dialog with Pilate | Dialog with Pilate | |||

| Pilate granted the body | |||||

| Nicodemus & Myrrh | |||||

| Clean | Bought the linen | Bought the linen | Cloth strips with spices as is custom of Jews | Bought the linen | |

| His own New tomb | no one ever been laid | Stone | Garden New tomb No one ever been laid | Stone | |

| Sit opposite the sepulchre | The other Mary (instead of mother of Joses) | Women from Galilee followed and saw tomb Returned and prepared spices Rested on Sabbath | Jewish day of preparation, tomb close at hand. | Mary Magdalene & Mary the mother of Joses saw |

The four versions are nearly uniform in length with the exception of Matthew, which is much shorter. The brevity of this account can be used to argue for Matthean priority. The shorter story in Matthew being one source used by the others. Those who argue for Markan priority must explain why the material found in Mark but not in Matthew is deleted in this passage. The overall story is consistent in each version, as is the location and function of the pericope in the overall passion narrative.

In Mark the burial scene ends with the closing of the tomb in verse 46.[6] Verse 47 is a transitional appendage to connect the scene of the woman at the tomb Sunday morning with the burial. The women take no role in the actual burial. Their presence explains their knowledge of the tomb location. Mark’s description of Joseph and his dealings with Pilate are consistent with a Jewish leader and a Roman official. There is no need to read Joseph’s waiting for the kingdom of God as being a disciple of Jesus. His behavior is consistent with Jewish piety and Pilate’s response equally logical.[7]

In Matthew Joseph is labeled a disciple. Discipleship is an important theme in the Gospel of Matthew. At the burial we see a disciple of Jesus performing the act of charity. But would a Roman official punishing an insurgent turn his body over to a follower? More likely Matthew is reading back into time a later full conversion of Joseph to faith in Jesus.[8] John takes the middle road by calling Joseph a secret disciple.

In Luke the description of Joseph follows his pattern of other pious Jews waiting for the coming of the messiah, Zechariah and Simeon. The emphasis is on his good moral character.[9] These are those expecting the coming of the messiah. He acknowledges Joseph’s association with the death of Jesus by belonging to the Sanhedrin but insists that Joseph objected to the crucifixion. As a good Jew waiting for the kingdom, he is ready to perform this good work of the burial and ripe for later conversion to disciple. [10]

John also calls Joseph a disciple and pairs him with Nicodemus. Joseph is not called a member of the council, but Nicodemus is introduced as such earlier in John’s Gospel. Together they provide a burial fit for a king, with a hundred pounds of spices and strips of linen cloth. The royal burial continues the Johannine kingship theme. Throughout the passion narrative in John, Jesus appears as king in an ironic form.[11] The return of Nicodemus provides a contrast in his faith. The first visit takes place in secret under cover of darkness. This return of Nicodemus is very public and in daylight. He has completed his journey to discipleship. [12] The Johannine story is preceded by the official Jewish request for accelerated deaths and removal of the bodies for the feast. The scene at the cross separates this request from Joseph’s request. [13]

There is no evidence of a Markan source for the Johannine material. Taken as a whole, the four passages suggest that Joseph was a leading member of the Sanhedrin that requested the burial of Jesus out of a sense of Jewish duty to the dead and the sanctity of the feast. He later grew into a full disciple of Jesus after the resurrection. John’s narrative then splits the request of Joseph from the “bad Jews” by the scene at the cross. Matthew and John read Joseph’s discipleship back into the time of the burial. Luke protects Joseph’s reputation as a member of the body that put Jesus to death by insisting he objected.

The exchange with Pilate and the centurion in verse 44 only exists in Mark. Pilate’s surprise at the death of Jesus in verse 44 would be an insertion into the Matthew account in the Matthean priority view. In the Markan priority view both Luke and Matthew delete this verse. The text of the narrative in Mark does not exhibit an unnatural transition. The statement is a credible one for a Roman authority. The quick death on the cross would support Gnostic claims that Jesus was not really dead. This would be a good reason to delete the verse from later writings. This verse would tend to support the Markan priority position.[14]

In verse 43 Mark places a long string of descriptions about Joseph. The sentence structure is awkward and rambling.[15] Matthew has a short clean description and Luke a longer but structured one. Both Luke and Matthew cleaning up the awkward structure are easily explained by Markan priority. If Matthew were the source for Mark and Luke, one would have to explain why Joseph’s title of disciple is dropped and replaced with member of the council. Matthew then promotes Joseph to disciple and Luke explains Joseph’s membership on the council by Joseph’s opposition to the death of Jesus.

Matthew, Luke, and John all refer to the tomb as a new one, details absent from Mark. The addition of this material to an existing source of Mark is more plausible than the deletion of the reference by Mark from a Matthew source. The Lukan and Johannine stress that no one else has been laid in the tomb fits the kingship theme of their gospels.[16]

Narrative Background

The burial narrative in Mark has elements that suggest Old Testament stories as subtle background. In 1 Kings 18:4-13 God’s loyal prophets are preserved in a cave while Elijah challenges the prophets of Baal. Likewise the body of Jesus is preserved in the cave/tomb. The third day finding of the empty tomb is reminiscent of the three day search for Elijah in 2 Kings 2:15-18. In both these actions Mark shows how those that appear to be in control really are not. [17] Just like Ahaz and Jezabel in the Elijah story, the Romans and Sanhedrin do not control God. In this model Joseph is the trusted servant of King Ahaz, Obadiah. Just as Obadiah serves the evil King against God’s servants, Joseph serves on the Sanhedrin that condemns Jesus. Yet they both move outside their masters to preserve God’s prophet.[18]

Historical background

Roman law forbids withholding the bodies of the crucified from their relatives for burial. However, we know from literature of the period that bodies frequently hung on the cross for many days. There are also reports of bodies refused to relatives or burned to prevent proper burial. Roman authorities would not generally remove the example of the crucified quickly. They very point of this method of execution is a very public example.[19]

Jewish custom requires a burial very shortly after the death even to the present day. Even those executed under the Mosaic Law were buried by sunset.[20] Josephus notes that the Roman treatment of the crucified disgusted the Jewish faithful. There is mention of times in the Old Testament where burial in the honored place of the family ancestors is denied, but never timely burial at all.[21]

There is no evidence outside the Gospels that the approach of a Jewish feast would compel the Romans to remove the bodies of the crucified. The approaching feast may increase Jewish desire for compliance with Mosiac law on the burial of criminals, but this situation is not directly attested. This fundamental conflict between the modus operandi of the Roman State and Jewish religious sensibilities lends an air of authenticity to this Gospel pericope.

The person of Joseph in Mark’s narrative occupies that position between Jewish authorities and full disciple of Jesus. This may indicate a person who later came to believe and be baptized after experiencing these events. But Crossan suggests this type of character is reason to doubt the existence of a real person in Joseph. That the burial narrative we have in Mark is a creative writing exercise to setup the empty tomb and the character invented. Crossan bases this claim on a literary dependency of Mark on Gospel of Peter and Mark’s creative expansion throughout. However, the character of Joseph is a weak one for a Christian argument. The stronger case would be made by having a clear enemy of the community burying and safeguarding the tomb. The more natural situation would be the burial by the family. If a character were invented he should have a more prestigious origin city. The invented character would not serve any good polemic purpose. The argument for the invention of Joseph collapses under it’s own weight.[22]

Lightfoot suggests that Joseph’s title as counselor makes him a priest. The Talmud refers to a council of priests in the Jerusalem temple that advise in matters of worship. This body was distinct from the Sanhedrin that condemned Jesus. The title counselor was applied to members.[23]

Patristic Use

Joseph of Arimathea is an obvious example of discipleship under difficult circumstances that the fathers loved to cite. In his commentary on Mark, Theophylact notes first Joseph’s risk to position, wealth and power by his request to Pilate. While commenting on the passage in Mark, he nevertheless does pull details of the scene from the parallel accounts.[24] In the same way Chrysostom and Ignatius hold up Joseph as the example of Christian boldness.[25] In a similar vein, Maximos the Confessor compares Joseph’s actions with Judas’ on the same day. The Christian is called to bury the Lord with honor in order to share in the Resurrection.[26]

The linen cloth provides a detail of significance for many of the Fathers. Theophylact compares this to our baptismal robe. Just as Christ is wrapped for Burial, we who share in that death with baptism are wrapped in the robe as well. We must wrap, fold, hold our linen, and not expose it to the unbelievers.[27] For Bede the shroud is a sign of simplicity, not the vanity of the rich. This simple burial of our Lord recounted by Mark, speaks to his humility in death.[28]

For Augustine placing Jesus in another’s tomb is symbolic of his death on our behalf.[29] For Theophylact the rock tomb becomes our soul. We must take the body of Christ, communion, and place it in the rock tomb, our soul. Using a word play between memory and tomb in Greek, he calls us to remember God.[30]

Maximos equates the tomb with both the present world and the heart of the Christian. The linen is the inner essence of sensible things and their goodness. The napkin (John’s version only) is knowledge and vision of God. Taken together all these allow the Christian to recognize the Logos. This recognition is not possible on our own.[31]

Patristic use of the pericope emphasizes the example of discipleship but also uses the details of the burial scene as an allegory for Christian life.

The passage in the liturgy of the Church

The Markan pericope of Joseph of Arimathea serves multiple times during the liturgical season surrounding Pascha. The passage fills the burial role in both Matins and Vespers on Great and Holy Friday. The story returns during the third Paschal Sunday and following week, where the story of the women and Joseph is commemorated. The Divine Liturgy is the service that commemorates the death and Resurrection of Christ on a regular basis. As such, the story of Joseph of Arimathea finds a home here as well. Joseph is found as a Saint in some Church Calendars on July 31.[32]

Strasti Matins on Great Friday contains twelve Gospel pericopes that stitch together the passion narratives of all four Gospels. The tenth reading is Mark’s passage. The eleventh and twelth readings are the parallel passages in John and Matthew respectively.[33] The hymnography of the service ends on the death on the cross. Liturgically the burial comes with vespers. The intervening Royal Hours are an extended meditation on the Glory of God in the mystery of the death on the cross. We end Strasti hearing of the burial of Jesus, but the in hymnography will wait until vespers.

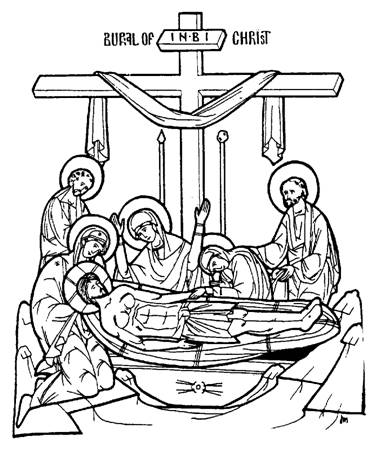

The Noble Joseph is the central character of Great Friday Vespers. We read a composite Gospel ending with the parallel account in Matthew. Joseph and the burial of Christ are now center stage. The body is removed from the cross and the burial shroud is taken in procession to the tomb. The hymnography of the service extol the actions of Joseph and Nicodemus.[34]

Holy Saturday matins Joseph of Arimathea shares the hymnographic limelight with Mary the mother of God. The example of Joseph as noble disciple weaves throughout the service and we again end with the veneration sound featuring both Joseph and Mary.[35] By vespers the scene has shifted to the abyss. Mary is still prominent but Joseph’s role has passed and we are marching beyond the burial towards the Resurrection.[36]

During the forty days of Paschal celebration we concentrate on a new theme each week. During the Third Paschal Sunday the theme of Joseph and the women at the tomb is commemorated. Mark’s version of events for the Burial and Sunday morning is read again. Throughout week we reprise many of the hymns to Joseph.[37]

During the Divine Liturgy Great Entrance, the gifts are brought from the table of preparation to the Altar. Placing them on the Altar the Priest prays that Joseph wraps the body in a clean shroud and places it in a new tomb while covering the gifts with the aer and incensing them.[38] The earthly body represented by the bread awaits the risen Lord. In a mystical way, the events of Holy Friday are made present. The risen Lord comes forth from the tomb on the altar.

In preparation for the funeral of a Priest or Bishop, Maximos’ allegorization of the holy napkin, mentioned above, is connected to the liturgical use of the aer. After vesting the priest the aer is placed over his face, just as the holy napkin in the burial account of John. Maximos equates the napkin with the vision of God, that his priestly servant is now experiencing. During the Divine Liturgy the aer covers the body and blood of Christ, during the funeral the aer covers those sharing in the priesthood of Christ.[39]

Conclusion

The consistent witness of all four Gospels and memory of the early Church bear witness to the essential historicity of the events in Mark 15:42-47. The narrative is internally consistent and the story is plausible with known events of the time. The Christian Church would gain little by a fabrication of this story and there would be other more satisfactory options should Mark engage in creative writing.

Joseph of Arimathea was likely a pious Jewish leader who was acting as a pious Jew in the burial of Christ. The later commemoration of Joseph as a disciple and Saint argue for his conversion to Christianity. But the events of the Gospels make his status as a disciple of Christ prior to the burial doubtful.

The Markan pericope is read twice during liturgical services. The parallel passage from Matthew makes an appearance on Holy Friday as well. The events of the passage in all four editions are in numerous hymns for Holy Friday, Holy Saturday and the Third Week of the Paschal season. These details provided much fruit for meditation by the fathers and contemplatives in the Church.

Bibliography

Aland, Kurt, et al. The Greek New Testament. UBS, NY, 1966.

Aland, Kurt. Synopsis of the Four Gospels 8th edition. German Bible Society, Stuttgart, 1987.

Belser, J. E. The History of the Passion. Herder Books, St. Louis, 1929.

Brown, Raymond. The Death of the Messiah. Doubleday, NY, 1994.

Brown, Raymond. The Gospel According to John. (Two volumes) Garden City: Doubleday, 1966.

Schaff et al. Nicene & Post Nicene Fathers. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1991.

Cyril of Alexandria, The Gospel of Luke. Translated by Payne Smith, Studion Publishers, 1983.

Danker, Bauer, Arndt, Gingrich. Greek Lexicon of the NT. University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Dickery, Warren. Mark, Matthew, & Luke, Human authors of the New Testament. Liturgical Press, Collegeville, 1990.

Fitzmyer, Joseph. Anchor Bible Commentary: The Gospel According to Luke. Doubleday, NY, 1983.

Hodges, Zane & Farstad, Arthur. The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text. Nelson, NY, 1982.

Holy Bible: The NET Bible (New English Translation), Biblical Studies Press, Dallas, 2001. [www.netbible.com]

The Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible. Nashville: Abington Press, 1986.

Kittel, Gerhard. Theological Dictionary of the NT. Eardmans, Grand Rapids, 1967.

Kudasiewicz, Joseph. The Synoptic Gospels Today. Alba House NY, 1996.

Inter-Eparchial Liturgical Commission. The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. Byzantine Seminary Press, Pittsburgh, 1965.

Lightfoot, John. Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica. Oxford University Press, 1859 (Hendrikson Reprint 1979)

Liturgical Commission of Sisters of St. Basil. Lenten Triodion. Uniontown, 1995.

Liturgical Commission of Sisters of St. Basil. Pentecostarion. Uniontown, 1986.

Mann, C. S. Anchor Bible Commentary on Mark. Doubleday, NY, 1986.

Meir, John. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. Anchor Bible Reference Library: Doubleday, NY, 1991.

Metzger, Bruce. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. United Bible Society, NY, 1971.

New, David. Old Testament Quotations in the Synoptic Gospels, and the Two-Document Hypothesis. Scholars Press (SBL), Atlanta, 1993

O’Collins, Gerald & Kendall, Daniel. “Did Joseph of Arimathea Exist?” in Biblica 75, 1994.

Oden, Thomas. Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: Mark. Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, 1998.

Palmer, GEH, Sherrard, Philip & Ware, Kallistos. The Philokalia. Farber & Farber, Boston, 1981.

Robinson, James. The Nag Hammadi Library. Harper, NY, 1990.

Roth, Wolfgang, Hebrew Gospel. Meyer Stone Books, Oak Park, IL, 1988.

Saliba, Philip Metropolitan (Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of N. America). “Procedures to be Followed upon the Death of a Clergyman.” http://www.networks-now.net/litresswroac/SVCClergy_Funeral.htm unknown date.

Swanson, Reuben. The Horizontal Line Synopsis. William Carey Library, Pasadena, 1984.

Taylor, Vincent. The Gospel according to Mark. St. Martin Press, NY, 1966.

Theophylact, Blessed. The Gospel of Luke. Translated by Christopher State. Chrysostom Press, House Springs, 1997.

Theophylact, Blessed. The Gospel of Mark. Chrysostom Press, House Springs, 1993.

Tikhon, Bishop (OCA USA). “Letter of Instructions #9 On Two Topics: I. About Censing II. The Burial of Priests.” http://www.holy-trinity.org/liturgics/tikhon.lit9.html 1996.

Wonderous is God in His Saints, St. Anthony the Great Orthodox Publications, Alamogordo, NM, 1985.

Footnotes

[1] Mann, p 656.

[2] Hodges, p 174; Verse 42 has a word inversion for hn paraskeuh in the Von Sodon group Kr , a spelling variant of prossabbaton for prosabbaton split the manuscipts. Verse 43 has a split between the verb forms hlqen and elqwn.

[3] Hodges, p 174; Verse 43 sees the omission of o and the insertion of ton. Verse 45-47 exhibit minor word changes. Verse 47 has variant name forms.

[4] Aland, The Greek New Testament, p 195. Metzger, p 121. Westtcott, p 112. Verse 44 substitutes hdh for palai in some manuscripts, Origen & Theophylact, a softening of Pilate’s remarks. The Diatessaron further softens “Is he truly already dead?”

[5] Taylor, p 599 & Brown, Gospel of John p 938

[6] Taylor, p 599

[7] Brown, Death of the Messiah, pp. 1215-1218.

[8] Brown, Death of the Messiah, pp. 1223-1227.

[9] Fitzmyer, p 1525.

[10] Brown, Death of the Messiah, pp. 1227-1230.

[11] Brown, The Gospel of John, p 960.

[12] Belser, p556.

[13] Brown, Death of the Messiah, pp. 1230-1232.

[14] Taylor, p 599

[15] Taylor, p 599 & Brown, Death of the Messiah, p 1213

[16] Fitzmyer, p 1525

[17] Roth, Hebrew Gospel, pp. 64-66

[18] ibid, p 124

[19] Brown, Death of the Messiah, pp. 1207-1209.

[20] Deuteronomy 21:22-23

[21] Brown, Death of the Messiah, p 1210.

[22] O’Collins, pp.239-240.

[23] Lightfoot, pp. 474-475.

[24] Theophylact, p 138.

[25] Ogden, p 238.

[26] Palmer, Vol II, p 126.

[27] Theophylact, p 139.

[28] Ogden, p 239.

[29] Ibid, P 238-239.

[30] Theophylact, p 139.

[31] Palmer, Vol II, p 126.

[32] Wondrous is God in His Saints, p 83.

[33] Liturgical Commission Sisters of St Basil, Triodion, pp592-593.

[34] Ibid, pp 628-630.

[35] Ibid, p 663.

[36] Ibid, pp. 663-670.

[37] Liturgical Commission Sisters of St Basil, Pentecostarion, pp. 86-129.

[38] Inter-Eparchial Liturgical Commission, p 29.

[39] Tikhon & Saliba.

Originally published: January 20, 2019